“Museums hold the physical and intellectual resources, abilities, creativity, freedom, and authority to foster the changes the world needs most.”

Sutton et al., 2017.

- WRITTEN BY MILO CAIGER-SMITH

Museums of all shapes and sizes have, over the last decade, with increasing speed and conviction, asserted their role in climate change responses, through declaring climate emergency, assigning climate-specific roles within their organisations, or publishing climate action plans that shape intended future sustainable actions.

When asked about the role museums should be playing in tackling the climate crisis, the response often centres around the privileged position museums have in inspiring public action and effecting positive behavioural change. Despite this, it seems that most museum declarations focus directly upon internal actions taken to reduce internal carbon emissions.

In my previous blog on the role of museums in a time of climate crisis, I highlighted the work of two organisations that aim to move the art world toward greater sustainability: Julie’s Bicycle (working with the entire culture sector) and the Gallery Climate Coalition (focusing primarily on private galleries). Both suggest that the first step an organisation should take is to calculate its own emissions, allowing effective targeted action to reduce them.

But if, as many believe, the power of art lies in its ability to inspire and elicit emotional responses, why does so much of climate action in museums focus primarily on the need to cut carbon emissions?

Walk the Walk

An internal culture of sustainability is, you could argue, a pre-requisite to more outward facing action: if an art museum is to act with authenticity as an influential voice on climate change, utilising the emotional power of art to further climate conversations, it must work first to enact sustainable internal changes, if only to avoid accusations of hypocrisy.

Lack of internal action opens museums up to criticism, and fear of criticism weakens a museums’ resolve to speak out: this is called ‘greenhush’. The Tate, for instance, has been able to realise a much stronger environmental voice since it ended its longstanding relationship with BP in 2016, in large part due to the actions of art collective Liberate Tate.

Liberate Tate, Human Cost, 2011. Photograph © Amy Scaife/Liberate Tate

If museums are to become vocal climate actors – something which is entirely necessary if they are to inspire public action – a sustainable core internal culture must first be established.

What does Climate action in Museums look like?

There are of course many measures that museums can take that are the same as any other organisation in other fields. For instance, museums can reduce internal emissions by up to 30% overnight simply by switching to a renewable energy provider. This blog, however, will discuss actions taken to reduce emissions that relate directly to specific features unique to the museum sector.

Central to a museum’s activity, and to a large extent to their carbon footprint, is the borrowing/loaning of artworks from museum to museum – particularly significant for museums with an international remit. Here it’s not just the traffic of things, but of people. Traditionally artworks have been accompanied by a courier to oversee the process; however, owing to travel restrictions caused by COVID 19, the Tate implemented a virtual courier system whereby the entire process of deinstallation, travel, and subsequent installation was organised via digital communication.

The exhibition Constable: A History of His Affections in England (2021) was successfully transferred to Tokyo with no couriers travelling, and installed by conservators connecting via Zoom, removing any emissions related to staff travel. While this change was initially forced by the COVID 19 pandemic, in January 2021 it was announced as company policy, and other institutions, such as the V&A, have indicated a desire to incorporate the policy into their working practices. Not only does this indicate a willingness for museums to overhaul traditional working practices; it is evidence of the spread of positive ideas from institution to institution.

Another common aspect I noted through interviews with museum professionals was an attempt to tackle the waste created through the production of exhibition displays themselves. Traditionally much of the display material from an exhibition would end up in a skip with little attention placed upon recycling.A British museum that is leading the sector in this field is the Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art, which has taken a creative, local, and collaborative approach to exhibition-making. Instead of constructing single-use exhibition spaces and plinths, a modular, re-usable system has been prioritised for displays, whilst any furniture or reusable products are donated to local charities.

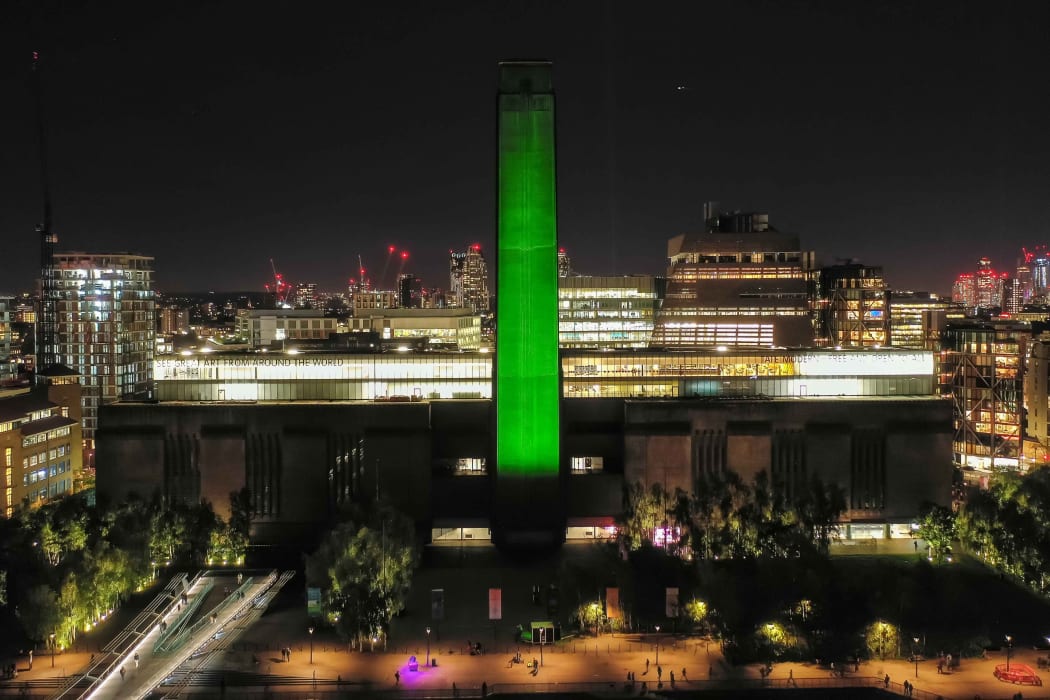

A final example of artists engaging in more sustainable practices is shown by Jenny Holzer’s recent light projections on major UK landmarks including Tate Modern and Edinburgh Castle. Holzer’s artwork is evidently climate focused: it highlights quotes from various global climate voices on the enormity of the challenge and the urgency of the need for global action, yet it is the extra planning within the setup that I’m highlighting here. The entire production was organised by Artwise curators based in the UK, in conjunction with Holzer’s studio in America, over Zoom. All projectors were LED lights connected to mains electricity. The strength of the message behind the artwork is only enhanced by extra steps such as these, taken to act sustainably.

These examples and other similar actions may seem simple, but for decades sustainability has been an overlooked principle in the museum sector - even by artists who have working consistently to produce art that is climate-focused. In highlighting such policies, I’d hope they could become commonplace rather than isolated examples of best practice.

Scope Three Emissions

So far, I have mentioned actions taken to combat ‘scope one’ emissions – those that the museum is directly responsible for - and ‘scope two’ emissions – those emissions that are produced indirectly – such as through the energy used within the building. But museums should be, and indeed often are, thinking about ‘scope three’ emissions – those emissions up and down its supply chain.

Tate’s climate declaration for instance, commits to “contractually require current and future suppliers to meet Tate’s environmental standards”. Once again, this relates to an outward projection of climate engagement, showing an institution pointing towards its own practices to encourage those that it works with to follow suit. As the museum sector is relatively small, supply companies often work with multiple organisations throughout the sector, so acting sustainably is becoming an expectation within the wider industry and providers’ failure to do so is increasingly likely to force museums to look elsewhere for services.

Visitor Travel Emissions

Having established the importance of practicing sustainable internal actions, the question now is: to what extent should museums be responsible for emissions generated by visitor travel? In the carbon audit provided by Julie’s Bicycle for Tate, 92% of Tate’s carbon emissions were said to originate from visitor travel alone. While this is particularly high in the case of Tate – owing to Tate’s status as one of the most popular modern art museums in the world, with audiences in the millions, Julie’s Bicycle’s formula assumes between 70-90% of most museums’ emissions come from visitor travel.

One could argue that the implication of this statistic is that for all the good work Tate has undertaken to reduce emissions across its multiple sites, it can only affect a reduction in 8% of its total carbon output. So why do museums tend to focus most of their efforts on this small proportion? And why do some carbon audits – such as that of the Galleries Climate Coalition – omit the larger impact of travel emissions altogether?

Firstly, it is difficult to quantify the extent of direct responsibility we can place on the institution. If visitors travel to London from abroad and visit a museum or gallery on their trip, can we really say that the museum bears full responsibility for the emissions related to their travel? A visitor may visit multiple galleries in one trip, among other attractions, so their travel may be counted multiple times in the carbon audits of different institutions.

Thirdly, tourism is ingrained into the business model of not just museums but the entire economy, especially within major cities such as London. Museums exist for their audiences; museums, as a business, are built upon increasing, or at the very least maintaining, visitor numbers; to ask museums to move away from a business model built upon foreign or long-distance travel, at a time when finances are already tight post-Covid, may sound unrealistic, even counterproductive.

Does this mean there is nothing museums can do to reduce emissions related to visitor travel? Several suggestions to combat high emitting modes of transports are proposed by Julie’s Bicycle such as offering incentives to low carbon transport options or installing electric car charging points. It’s important, surely, to recognise that part of the solution lies outside of the control of the museum. Improvements in low carbon transport, be that local public transport or nationwide systems, is beyond the power of museums, though museums can and should lobby for these necessary improvements. Ultimately, there is no objective right answer to this question, yet there are several potential avenues worth exploring.

Local or International?

One area of museum practice that, on the surface, may seem particularly polluting are the large international tours of exhibitions. Flying whole shows around the globe undoubtedly has a large carbon output. Yet, these exhibitions are often the major attraction to large numbers of foreign tourists – particularly within the London-based large national museums. One could argue that sending exhibitions on tour abroad – particularly large ‘blockbuster’ shows – might allow international audiences to see them while remaining at home; would that be preferable? But is it even doable? Is the urge to travel so easily manipulated?

Maybe, too, transportation of an entire show from one museum to another is better in terms of emissions than if each museum attempted to curate an entirely separate show. Even here, though, the nature of the transport needed varies. Instead of borrowing individual artworks from multiple lenders across the globe, the works in a recent show at the Tate Modern, The Making of Rodin, were borrowed almost entirely from a single lender - the Rodin Foundation in Paris. As they are all from the same place, the carbon emissions from consolidated transport were much reduced.

While the examples I have given tend to focus on the touring of large international exhibitions, the same logic can be used to apply for regional touring domestically. Owing to the large carbon emissions related to the transportation of art and people, new methods must be considered that are unique to the specific circumstances of the exhibition or museum. The result may be aiming to tour, aiming to borrow art all from the same lender, or forcing museums to ask themselves: is the piece of art or exhibition worth the carbon output in the first place?

The Community-Based Museum

One common criticism that goes hand in hand with a challenge towards foreign travel is that museums’ local communities have tended to be overlooked.. Evidently, if museums were to shift their audience towards a more local audience, emissions from travel would decrease. Instead of seeing a community focus as a pragmatic choice designed to reduce emissions, one could argue that it should be considered as a fundamental pillar of the museum in the first instance. Museums are funded by the taxpayer, so do they not have a duty to present exhibitions and programs that speak to the museums’ local communities, instead of programs developed with international appeal in mind?

A good example of a museum seeking to engage with these discussions is the V&A’s new outpost into the Olympic Park in London, V&A East. Underpinning the design behind this expansion is a strong commitment to engage traditionally underrepresented audiences in a less economically developed part of London. New audiences need to feel involved in and understand the direction and decision-making through extensive consultation and outreach programs. Instead of seeing a community focus as a pragmatic choice designed to reduce emissions, it can also be considered as a fundamental pillar of the museum’s mission.

External render view of the new V&A East Museum at Stratford Waterfront, designed by O'Donnell + Tuomey. © O'Donnell + Tuomey / Ninety90, 2018

Alongside providing greater representation for traditionally underrepresented groups, a more local audience who visit numerous times over a year could allow the construction of a stronger relationship between the audience and the institution. When it therefore comes to engaging in climate, in terms of promoting sustainable living and effecting broad behavioural change, the museum is in a far stronger position. How effective can a museum be at influencing the beliefs and actions of a visitor base, the majority of whom are unlikely to attend more than once a year?

At a purely logistical level, in the wake of Covid and the impact the pandemic has had on international travel, it may no longer make sense in terms of risk, to base a museums financial stability on a large proportion of international visitors. Carbon emissions apart, if the sector can no longer bank on large numbers of foreign tourists, then to shift, at least slightly, to a greater onus on local engagement makes financial as well a sustainable sense.

Growth or De-Growth

Museum expansion, though; is this the answer? A model based upon perpetual growth was famously adopted by the former Guggenheim, New York Director Thomas Krens, as early as the later 1980s; Krens famously followed the principle formulated by George T Lockland in his publication, ‘Grow or Die: The Unifying Principle of Transformation’ (1973). The principle of necessary and continuing expansion has underpinned the proliferation and development of the museum sector for a large part of the last forty years.

It is all well and good that museums such as the V&A East are instilling a greater sense of their local community into their core principles. Yet, in a time of scarce resources, museums ought to increasingly question whether they can legitimise continued physical expansion. The digital realm has long been acknowledged as an essential part of the museum’s future, surely climate emergency, not to mention the restrictions related to Covid, make future thinking about the digital realm all the more important?